Prioritizing Stressors: Using Family Stress Theory to Allocate Scarce Crisis Nursery Resources to Poor Families

Abstract

This paper explores the ways Crisis Nurseries can utilize the Family Stress Theory Double ABC-X model to fairly allocate limited services to families in need. By exploring the ways a Crisis Nursery can increase a family’s resources when facing a stressor, the author aims to encourage a model which measures the intersection of minimizing harm and maximizing well-being in families facing crisis. This tool can be used to assign standardized scores to families seeking services that enable Nurseries to reliably allocate limited resources to those who will experience the greatest benefit. Further, implications for why poor families experience greater risk of crisis when faced with stressors that would be minor inconveniences for middle-class families and how the growth of Crisis Nurseries as a concept can be encouraged while seeking to maximize the benefit of their limited resources are discussed.

Prioritizing Stressors: Using Family Stress Theory to Allocate Scarce Crisis Nursery Resources to Poor Families

Introduction

In the United States, living in poverty is likely to impact everything from one’s cognitive decision-making ability to the way a family reacts to stressors that would be minor inconveniences in a more financially stable home (Shah et al., 2012). Poverty is a constant strain on attention and resources and magnifies problems into catastrophes. These catastrophes can often be avoided or mitigated with relatively small amounts of cash. Many working poor families obtain cash for unexpected expenses through high-interest payday loans, finding themselves in a predatory cycle that makes it less likely they will be able to engage in more traditional and less exploitative financial services (Koku & Jagpal, 2015). When a middle-class family has an unexpected expense of about $100, it is likely they can cover it with their own resources and even more likely they can access banking or personal relationships to obtain the funds without predatory lending conditions. When a poor family has an unexpected $100 expense, it is possible, even likely,that this expense will set them back from any financial goals they have been able to envision for themselves, and make ever flimsier the bootstraps by which they are meant to be pulling themselves up.

The figure of $100 is meaningful because it is such an enormous amount to gather for individuals living in poverty and such a minor amount for more financially stable families. It is also an amount that is the minimum many childcare professionals will accept for showing up to perform in-home childcare. As a private in-home childcare professional in Washington, DC,a major East Coast city that has a high rate of poverty,$100 is what I earn for an unexpected job of 3–4 hours. In other words, if a family finds they unexpectedly need an afternoon of childcare for any reason and do not have an extant network of people who can perform this service for them, hiring someone is an unanticipated expense of about $100.

Needing childcare on a temporary and unexpected basis is different from ongoing childcare needs that a family may arrange to engage in ongoing scheduled work or other duties. When I show up to care for middle-class families for three hours that are not part of an ongoing childcare schedule, I am usually making it possible for them to attend an event, go on a date night, or run necessary but nonurgent errands. When a poor family needs a few hours of childcare unexpectedly, the stakes are often much higher, from the possibility of attending a potentially life-altering job interview to fulfilling court-mandated drug treatment that will solidify family stability.

Programs exist to subsidize long-term, full-time childcare in cities such as Washington, DC. A gap, however, exists in supporting short-term, immediate-need services for families for whom a relatively small amount of childcare could allow them to increase family stability and success and prevent catastrophe. The public defender’s office in Arlington County, VA, acknowledges that as many as half of its clients suffer for lack of access to small amounts of childcare (B. Haywood, personal communication, January 14, 2022). Similarly, parents seeking treatment for mental illness or substance use disorder can find lack of childcare destabilizing (T. Salame, personal communication, September 24, 2021). Access to quality childcare for short-term needs is out of reach for many poor families, with disastrous outcomes and at a deep cost to their potential (Belt, 2019; Berkon, 2020). It is evident that investing in childcare is a proven and effective way to impact outcomes and potentially lift families out of poverty, yet need-based childcare on a short-term basis is nonexistent for most poor Americans (Hufkens et al., 2019). Research and observation consistently show that the free market is an insufficient method for managing childcare markets, especially for poor families (Lloyd et al., 2013).

Remarkably suited to meet this particular need, the model of Crisis Nurseries is a tested solution to the problem of affordable, acute-need, short-term childcare for poor families. They are underutilized, and their reach remains relatively small. As of 2019, only 48 recognizable Crisis Nurseries existed in the United States, heavily clustered in Illinois (which boasts seven of the 48), meaning 41 such facilities labor to meet the needs of the other 49 states (Kendal & Perille, 2019). With a vision of encouraging growth of this resource in the future, I accept the reality of limited resources relating to Crisis Nurseries in the present, which ultimately leads to asking one of the most uncomfortable of questions: How can limited access to a resource for which the need overwhelms the available services be fairly allocated?

Family Stress Theory is an appropriate lens through which to evaluate which families will experience the greatest benefit and most significant reduction of harm when allowed access to Crisis Nursery services. Through a review of extant literature about the role of Family Stress Theory in interpreting negative family events, as well as the services Crisis Nurseries can reliably provide, I explore the situations in which access to a Crisis Nursery can have the greatest positive impact on family experience and stability.

Literature Review

The review of existing literature relevant to the research question focuses on two areas: the role and effectiveness of Crisis Nurseries and Family Stress Theory as it relates to childcare access.

The Role and Effectiveness of Crisis Nurseries

Crisis Nurseries exist to mitigate several stressors that, without access to relatively small amounts of childcare, will cause families to enter crisis and prevent actions that will increase family stability. In a three-year survey of five Illinois Crisis Nurseries which ended in 2003, Cole et al. (2005) quantified reasons for accessing services distributed in the following ways: Job/School Obligations (34%), Parental Stress (31%), Medical Related (12%), Substance Abuse (7%), (6%), Domestic Violence (2%), Court Related (3%), Mental Health (2%), Public Support Services (2%), and Other (1%). While the reasons for accessing Crisis Nursery services are varied, the impact on those who can access these services is a nearly universal positive. Among caregivers surveyed yearly over the course of three years after accessing Crisis Nursery services, at the three-year mark 90% reported a “decrease in parental stress,” 98% reported they were at less risk of maltreating their children, and 96% reported “improvement in parenting skills” (Cole et al., 2005).

Nursery Way, a trademarked Crisis Nursery program establsihed through a collaboration of researchers at the University of Minnesota’s Institute of Child Development and Harvard University’s Center on the Developing Child, was developed specifically to serve families who need substantial, but still temporary, assistance with childcare to avoid adverse outcomes for the children or the family (DePasquale et al., 2020). The programming focuses on mitigating risk factors for adverse outcomes (such as poverty, unemployment, and generational patterns of abuse) with protective factors (such as parental resilience, community involvement, and education on child-rearing techniques), while interacting with families in a respectful and affirming manner. Centers using the Nursery Way protocol also emphasize the health of the providers in Crisis Nurseries and enlist them in a holistic program of developing the centers as sites of calm and community for parents, children, and providers. Pilot studies demonstrate that staff training in mindfulness-based stress-reduction techniques for children in their care have a ripple effect. When children are better able to self-regulate and mitigate chronic stress, childcare providers are more content, and parents are happier (and therefore more effective and peaceful) (DePasquale et al., 2020).

Crisis Nurseries are frequently used as respite care for foster families, who do not have the luxury of asking unvetted friends or neighbors to babysit for the children in their care. Access to Crisis Nursery respite care has a positive effect on foster children and their foster families, increasing longevity of service by foster parents and substantially increasing the likelihood that a child in foster care will be reunited with their biological family (Cole & Hernandez, 2011). Access to Crisis Nursery services by families in crisis also has a preventive effect on foster care placement. Families who can access Crisis Nursery services, particularly those that include one-on-one case management, education, and connection to outside social services, are significantly less likely to subsequently relinquish their children to foster care (Crampton & Yoon, 2016).

Family Stress Theory and Childcare Access

Childcare is a stressor for all families—not just those living in poverty—but the impact of limited access to quality childcare has a wider effect for poor families. An example is the disparate experience of school holidays as perceived by poor and middle-class families. While middle-class families largely see school holidays as a pleasant opportunity for children to engage in enriching extracurriculars or for the family to spend time together, for poor families school holidays are a source of stress, expense, and anxiety primarily due to lack of childcare and food insecurity (Stewart et al., 2018). This is a good example of how the same stressor—a day when children would usually be in school but are not—becomes a minor inconvenience or even an opportunity for middle-class families and a destabilizing crisis for poor ones.

Disruption to routine is also impactful to parents, particularly poor parents who have limited ability to pay for childcare services when they need to manage or take steps to improve their own lives. Disruption to treatment for substance use disorder has been a particularly significant stressor for caregiving parents during COVID-19, when many in-person treatment options that contributed to individual and family stability were halted (Huhn et al., 2021).

Lack of childcare is not the same thing as a pandemic, but it has a similarly limiting effect on parents’ ability to access care, since parents cannot bring children to most addiction treatment services and cannot leave children alone. For this reason, the disruptiveness of missing substance use disorder treatment due to COVID-19 can be extrapolated toward understanding the comparable disruptiveness of missing any kind of healthcare due to lack of childcare access. In these cases, the initial stressors are different, but the lack of resources and responses are similar. COVID-19 prompted increased research regarding how family stress impacts levels of child maltreatment and can similarly be interpreted as an analog for understanding how lack of access to childcare (made worse by the COVID-19 crisis) can increase child maltreatment. COVID-19 increased parental stress due to factors that the pandemic has in common with lack of childcare access: inability to attend healthcare appointments by the parent, increased partner violence, economic anxiety and instability, and lack of respite from childcare responsibilities (Wu & Xu, 2020).

Family resilience is a fundamental facet of surviving any stressor and exists in two forms: as a capacity and as a process (Patterson, 2002). To understand the process of family resilience, one must understand the degree to which a stressor differs from ordinary family life and the ways families make meaning from their stressors. Families thrive when they can make meaning out of stressful events (Patterson & Garwick, 1994). Having short-term, free childcare as a resource during a stressful event (including, for example, when transitioning from a violent home, interviewing for a new job, or accessing treatment for a substance use disorder), increases the likelihood that the stressor will resolve into a positive outcome and potential increase in stability and health for the family, which in turn creates positive meaning surrounding the stressful experience.

Theoretical Perspective

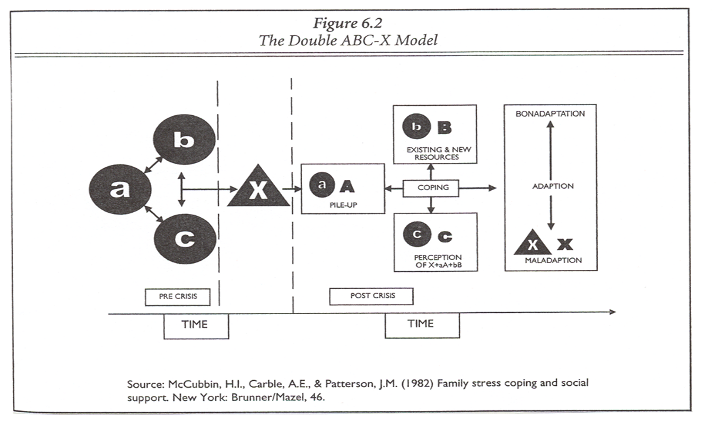

Using information and Figure 6.2 (Smith & Hamon, 2017), it is possible to understand Family Stress Theory as the most appropriate lens through which to evaluate the need a family experiencing a particular stressor may have for Crisis Nursery services and how it compares to the needs of families experiencing different stressors.

Figure 1: The Double ABC-X Model

The Double ABC-X model of Family Stress Theory is a tool for applying visual logic to the multifaceted experience of a family responding to a stressor event. Since acute childcare needs are by definition temporary, they are usually in response to an immediate and identifiable stressor which has the potential to be mitigated or resolved. This makes Family Stress Theory and its model a particularly useful tool for evaluating the need of an individual family for Crisis Nursery services and, as importantly, the potential positive impact such services will have on outcomes for the family post-crisis. I will explain the different facets of the Double ABC-X model using a hypothetical parent who would be a target recipient for Crisis Nursery services: a parent who has been arrested for a drug-related offense and can avoid jail time and increase their health by attending all required court dates and receiving treatment for substance use disorder. This hypothetical parent is motivated to complete these requirements but faces a challenge in finding care for their children while they attend court dates and treatments.

a Factor: Stressor event

The “a Factor” is the identifiable event which precipitates any reaction or crisis. In the context of families seeking Crisis Nursery services, the stressor event is likely to be one of the common reasons families seek acute-need childcare: court appearances or obligations, health issues needing care, parental or foster-parental stress, domestic violence, work, or school obligations, or accessing other social services (Cole et al., 2005). In the hypothetical, the stressor is a parent’s arrest for a nonviolent drug charge and subsequent navigation of the criminal justice system with the goal of avoiding jail time.

b Factor: Resources

An inventory of the resources a family has in response to the stressor event results in a list of potentially mitigating influences that can prevent the stressor from erupting into a crisis. A family needing acute childcare would list among its resources family, friends, and neighbors who are able and willing to care for children at a cost that is affordable to the family facing the stressor, as well as funds to hire a professional babysitter or utilize a paid drop-in childcare center.

c Factor: Definition of the event/perceptions

Families give meaning to events, both positive and negative. A family with more resources to mitigate the crisis resulting from a stressor is understandably more immediately able to imbue a stressor with positive meaning. For instance, a parent who can make all of their court appearances and court-mandated substance use treatment appointments because they have safe and reliable childcare for those times may see the arrest that led to this treatment as an opportunity to receive treatment which stabilizes them and their family as a whole. A parent who faces increased penalties and possible loss of their children when they are not able to attend court dates or treatment will naturally perceive the arrest as a destabilizing catastrophe with negative effects on their entire family.

x: Stress or crisis

Stress is a reaction to the stressor which results in a change in the functioning of the family (their equilibrium) but does not bring family functioning to a complete standstill or result in unmitigated catastrophe. Crisis is a reaction in which the family cannot function sustainably and is not able to regain equilibrium. In the context of Crisis Nurseries, a family will experience stress surrounding a drug arrest if the arrested parent is able to complete court-mandated treatment to a judge’s satisfaction and avoid jail. The family will experience crisis if the parent relapses or is put in jail.

aA Factor: Pileup

Pileup refers to additional stressors that result from the initial stressor. If the initial stressor that interrupts family equilibrium is an arrest for a drug offense, pileup stressors can include the financial stress of paying for childcare to cover court appearances and treatment, increased penalties if the parent cannot meet these obligations, disruption of the family if the parent is sent to jail, and the negative effects of relapse or ongoing active addiction.

bB Factor: Original and additional resources

Original and additional resources are resources listed in the initial inventory of the “b Factor” as well as additional resources that materialize as the family continues to navigate the aftermath of the stressor.

cC Factor: Perception of the stress or crisis and family response

This factor is the sum of the family’s perception of aA and bB factors. A family will interpret the initial event as well as subsequent resources, reactions, and the ability to prevent crisis. A parent who accessed Crisis Nursery services to help navigate the aftermath of a drug arrest may see these services as a positive indicator of the quality and reliability of their community. Many parents who interact with Crisis Nurseries credit this experience as their first positive interaction with a “system” and one which equipped them to expand their well-being and the well-being of their children (DePasquale et al., 2020). A family who has this kind of positive experience accessing Crisis Nursery services after the trauma of an arrest can potentially perceive the entire experience —the stressor and the response—as a positive step toward increased family stability and community connection.

xX Adaptation: Family response to the stress and post-crisis reaction

Following the experience of a stressor and the subsequent steps of the Double ABC-X model, a family will land on a spectrum from low to high adaptation. In most of the situations in which parents access Crisis Nursery services, there is potential to increase family well-being not just mitigate family harm. A family that has a positive experience navigating a stressor and its aftermath thanks to a Crisis Nursery is likely to fall at the high end of adaptation and emerge healthier, stronger, and more stable from the experience.

The goal of a Crisis Nursery viewed through the lens of Family Stress Theory would be to prevent pileup while enabling positive meaning-making from initial stressors and preventing stresses from becoming crises.

Synthesis of Theory and Research

Crisis Nurseries exist to provide acute-need, short-term childcare to poor families. The reasons families need to access Crisis Nursery services are varied, and the need vastly outweighs availability. Circumstances which may cause a family to utilize a Crisis Nursery include job interviews or training, court-mandated service or drug treatment, appearances in court, accessing physical or mental healthcare, respite for foster parents, and safe care of children while a parent arranges evacuation from a violent home. These circumstances are varied but have two features in common. First, they cannot be effectively or appropriately navigated without childcare. Second, not managing them adequately will have a negative impact on family health and stability.

When using Family Stress Theory to quantify the need that a family has for Crisis Nursery services and the positive impact that Crisis Nursery services can have on the outcome of a stressor event, it is helpful to make a succinct list of stressors people who already use Crisis Nurseries cite as reasons for accessing their services. It is effective and useful to put the reasons behind need for acute childcare (stressors) into five broad categories, of which the proportion of Crisis Nursery families who fall into each category are roughly as follows:

- Job/School Obligations (including job interviews, training, unexpected shifts) (34%)

- Parental Stress (including Foster Parent respite and child maltreatment prevention) (31%)

- Medical Care, Mental Health Care, or Substance Use Disorder Treatment (21%)

- Home Crisis or Domestic Violence (8%)

- Court Related or Accessing Public Support Services (5%) (Cole et al., 2005).

Pinpointing the particular stressor is the essential first step to evaluating an individual’s comparative need for Crisis Nursery services (aA) and the positive impact the services can have on outcomes (cC and xX). It should be noted that the above percentages are not relevant to quantifying the need of a family according to Family Stress Theory, since each family is evaluated individually based on the severity of their stressor and the potential severity of the outcome. The percentages of frequency are offered as an indicator that a person evaluating family need should take care to be well versed in the stressors that fall under the more frequent categories because they are more likely to encounter these stressors when evaluating families. In other words, slots in a Crisis Nursery are not disproportionately allocated to families facing job and school responsibilities simply because there are more of them than families facing home crisis or domestic violence, since each case is evaluated individually with the Double ABC-X model for the effectiveness of Crisis Nursery intervention. However, an evaluator should take time to familiarize themselves with the types of job and school obligations that lead to need for Crisis Nursery services and the outcomes that can be anticipated, since they are likely to see (and need to evaluate) a great deal of cases that fall into that category.

When evaluating potential client families for a particular Crisis Nursery, intake specialists can use Family Stress Theory in general, and the Double ABC-X model in particular, to visualize the way that accessing a precious spot in a Crisis Nursery is likely to mitigate harm and increase well-being in a family facing a stressor event. Besides simply providing childcare, the most effective Crisis Nurseries are staffed with caseworkers who direct client families toward other public and private resources that can benefit their unique situations (DePasquale et al., 2020). To maximize this partnership between acute-need childcare and long-term casework, an organization-wide familiarity with Double ABC-X models, augmented by a robust understanding of likely potential outcomes from different stressors for families in poverty, can help individual Crisis Nurseries prioritize and provide the most quality service per hour of childcare they have to offer.

COVID-19 has had a magnifying effect on the childcare crisis in the United States. Stressors experienced by families in response to COVID-19 are often analogous to those experienced by families who do not have access to childcare. The sheer number of those impacted by COVID-19 interruptions allows for robust research that can be extrapolated to understand the augmented response to stressors by families who struggle to find childcare to meet short-term, acute needs. COVID-19 is the initiating event for an increase in child maltreatment, partner abuse, and family stress behaviors more generally (Wu & Xu, 2020). If we know, through the enormous amount of data and research that the scale of the COVID-19 crisis has made possible, that families experience negative responses to stressors when they cannot access services, and we know that they cannot access services without childcare, then knowledge gained from research into COVID-19–related stress is transferrable to understanding Crisis Nursery need.

Discussion

Most people, even those in the childcare field, are unfamiliar with Crisis Nurseries as a concept and are unaware that they exist. This is due largely to their scarcity, since in a country of 332 million, it is understandable that a person may have never encountered one of only 48 facilities (Kendal & Perille, 2019). The need, however, is immediately apparent to anyone who understands the challenges of raising a family, let alone raising a family while poor. Unexpected childcare need can upend the best-laid plans in the most financially insulated family, but it is the very poor who experience crisis and upheaval of their family stability for want of a few hours of childcare.

In my research, I spoke with two individuals who confirmed to me that they see meeting this need having a real impact in their distinct lines of work. Mentioned in the introduction, Tony Salame (a psychiatric nurse who treats substance use disorder) and Brad Haywood (the head of the Public Defender’s office in a populous Virginia county) shared specific anecdotes and larger generalizations about how access to short-term childcare would drastically improve outcomes for their patients and clients experiencing stressors. These outcomes, and whether they are positive or negative, invariably ripple out to families and can cause generational impact (Cassiman, 2006). Neither professional had ever heard of a Crisis Nursery, and both enthusiastically reinforced my belief that a Crisis Nursery in the Washington, DC region would have a dramatically beneficial impact on families with whom they interact. Both shared a belief that most people do not understand what a difference small amounts of free, on-demand childcare would make for poor families navigating substance use disorder treatment or the criminal justice system. When $100 worth of childcare can, without exaggeration, mean the difference between a parent relapsing and not relapsing, or going to jail and not going to jail, or losing their children and not losing their children, it is a problem worth our notice.

With this anecdotal data, along with the robust evidence supporting Crisis Nurseries available in the literature, it ought not be a challenge to convince the average person that Crisis Nurseries are an efficient investment of dollars toward family stability and well-being. But this knowledge is not consistent with the reality in which we live. In a country with 48 Crisis Nurseries and enormous need, most communities will not be served by a Crisis Nursery at all, and those who are will experience more demand than individual Nurseries are able to meet. Because the Double ABC-X Model evaluates the effect of an individual stressor on an individual family’s equilibrium, it is a useful tool for comparing the relative beneficial impact a spot in a Crisis Nursery can have for different families navigating different stressors. It is uncomfortable to have to speak of rationing services to people who so desperately need them. But while advocates of Crisis Nursery growth can ardently wish that this discomfort will inspire a meaningful investment in the services, those whose responsibility it is to the daily functioning of a specific Crisis Nursery location do not have the luxury of avoiding it.

The practical implementation of the Double ABC-X model in evaluating relative need for Crisis Nursery services among those seeking them can be employed in individual Crisis Nurseries as a tool for fairly and confidently allocating limited services to families who will experience the largest intersection of harm reduction and increased well-being when the acute-need childcare is introduced as a resource on the families’ individual Double ABC-X models. Those who are responsible for determining service allocation must become familiar with probable outcomes of a multitude of situations, do robust evaluation of an individual family’s existing resources, and assign each family a score based on the evaluator’s understanding of their situation supported by standardized training which ensures that evaluators are working from a common curriculum. The common curriculum will allow scores assigned by different evaluators to be compared to one another when ranking the benefit families will receive from Crisis Nursery services.

Family Stress Theory is relevant to the problem of allocating Crisis Nursery services because the theory’s strengths lie in its understanding of how small stressors can have vastly different outcomes depending on the resources available to a family. Crisis Nurseries should be among those resources, and in doing so prevent stress from becoming crisis. Crisis Nurseries have the pleasant responsibility of not only mitigating family harm but increasing family well-being, particularly in the ways that families make meaning out of stressful events. In turn, more stable families are able to become a resource to other families, creating networks that can offer short-term childcare to one another. Family Stress Theory shows that resources beget resources, and stability begets stability, and both together beget positive outcomes for families facing stressful events. When stressors are able to become moments of positive transition for families rather than initiators of crisis, the positive impact ripples outward and onward. A Crisis Nursery will never be limited in impact to the hours of childcare it provides but will always have the potential to initiate a virtuous cycle that improves the experiences of families and communities. The resources of a Crisis Nursery, however, are limited, and it is with the goal of maximizing the positive effect their limited resources can have that I explored the use of the Double ABC-X model when evaluating where to direct them.

Conclusion

In approaching the issue of Crisis Nurseries, I began with the understanding that need for their services overwhelmingly exceeds their ability to deliver them. The literature is unanimous in its endorsement of Crisis Nurseries as a societal good and a highly cost-effective and impactful way to help prevent difficulties from becoming full-blown crises in poor families. Crisis Nurseries, however, are rare, and an understanding of their existence and usefulness is rare, as well. Since there is more need than there is ability to meet it, it is inevitable that individual Crisis Nurseries will have to make choices about who to serve when multiple families seek limited spots in a schedule of acute-need childcare. After exploring Family Stress Theory and the way it relates to the need for accessible and affordable childcare, I determined that the theory’s Double ABC-X model could be a useful tool for evaluating the relative benefit families with different resources facing different stressors would experience when allocated the services of a Crisis Nursery. A beneficial use of the model would require a common evaluation curriculum administered to each evaluator in a particular Crisis Nursery, to ensure the comparability of scores awarded by different evaluators. I regret the scarcity of service that mandates such precise evaluation and hope that the impact of Crisis Nurseries will be more widely explored in the literature and experience mainstream attention that will increase interest in and funding of the concept.

References

Belt, D. (2019, March 2). How much you need to earn to afford a home in Washington DC metro. Washington DC, DC Patch. https://patch.com/district-columbia/washingtondc/how-much-you-need-earn-afford-home-washington-dc-metro

Berkon, E. (2020, January 9). For some D.C. parents, it’s too expensive to work. NPR.org.https://www.npr.org/local/305/2020/01/09/794851835/for-some-d-c-parents-it-s-too-expensive-to-work

Cassiman, S. A. (2006). Toward a more inclusive poverty knowledge. The Social Policy Journal, 4(3–4), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1300/j185v04n03_06

Cole, S. A., & Hernandez, P. M. (2011). Crisis nursery effects on child placement after foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(8), 1445–1453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.012

Cole, S. A., Wehrmann, K. C., Dewar, G., & Swinford, L. (2005). Crisis nurseries: Important services in a system of care for families and children. Children and Youth Services Review, 27(9), 995–1010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.12.023

Crampton, D., & Yoon, S. (2016). Crisis nursery services and foster care prevention: An exploratory study. Children and Youth Services Review, 61, 311–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.01.001

DePasquale, C. E., Parenteau, A., Kenney, M., & Gunnar, M. R. (2020). Brief stress reduction strategies associated with better behavioral climate in a crisis nursery: A pilot study. Children and Youth Services Review, 110, Article 104813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104813

Hufkens, T., Figari, F., Vandelannoote, D., & Verbist, G. (2019). Investing in subsidized childcare to reduce poverty.Journal of European Social Policy, 30(3), 306–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928719868448

Huhn, A. S., Strain, E. C., Jardot, J., Turner, G., Bergeria, C. L., Nayak, S., & Dunn, K. E. (2021). Treatment disruption and childcare responsibility as risk factors for drug and alcohol use in persons in treatment for substance use disorders during the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Addiction Medicine, Publish Ahead of Print. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000813

Kendal, A., & Perille, C. (2019, August 21). Safe Havens in Times of Need: The Role of Crisis Nurseries. SchoolHouse Connection. https://schoolhouseconnection.org/safe-havens-in-times-of-need-the-role-of-crisis-nurseries/

Koku, P. S., & Jagpal, S. (2015). Do payday loans help the working poor? International Journal of Bank Marketing, 33(5), 592–604. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijbm-11-2014-0164

Lloyd, E., Penn, H., & Sosinsky, L. S. (2013). Childcare markets in the US: supply and demand, quality and cost, and public policy. In Childcare markets: Can they deliver an equitable service? (pp. 131–150). essay, Policy Press.

Patterson, J. M. (2002). Integrating family resilience and family stress theory. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(2), 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00349.x

Patterson, J. M., & Garwick, A. W. (1994). Levels of meaning in family stress theory. Family Process, 33(3), 287–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.1994.00287.x

Shah, A. K., Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2012). Some consequences of having too little. Science, 338(6107), 682–685. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1222426

Smith, S. R., & Hamon, R. R. (2017). Exploring family theories (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Stewart, H., Watson, N., & Campbell, M. (2018). The cost of school holidays for children from low income families. Childhood, 25(4), 516–529. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568218779130

Wu, Q., & Xu, Y. (2020). Parenting stress and risk of child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: A family stress theory-informed perspective. Developmental Child Welfare, 2(3), 251610322096793. https://doi.org/10.1177/2516103220967937